Built to Burn Out

How the economy is stalling, the startup playbook is breaking, and speed is the wrong response to scarcity

The Accademia dei Lincei is one of the oldest and most prestigious scientific institutions in Europe. Located in the Trastevere district of Rome, it is perhaps most famous for being the academic home of Galileo Galielei. It is as beautiful as it is intimidating

On this particular day in April 1968, the Accademia was hosting a carefully curated group of thirty guests drawn from all corners of the globe. Scientists, economists, civil servants, humanists, and business people, all gathered together for a single purpose.

And what was the topic for discussion at the Accademia?

Nothing less than the present and future predicament of humankind.

The conference organisers shared a vision of “global dangers that could threaten mankind such as over-population, environmental degradation, worldwide poverty and misuse of technology.”

Sound familiar?

This meeting was their one shot at galvanising European thinking about these global challenges. But, despite the best efforts, the days quickly descended into technical and semantic debates. By their own admission, the meeting was a ‘monumental flop’.

Disheartened by what they had seen, the core team decided to go around the obstacles and forge ahead regardless. So, with an initial group of just four people, the famous ‘Club of Rome’ was born.

THE WORLD PROBLEMATIQUE

The Club of Rome was committed to action, and their first project was ridiculously ambitious.

They wanted to understand what would happen if we continued our path of exponential economic and population growth, within the finite system of our earth’s natural resources. So, they asked a group at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to develop a mathematical model that could describe the ‘World Problematique’ that be used as a guide for future actions.

MIT accepted the challenge.

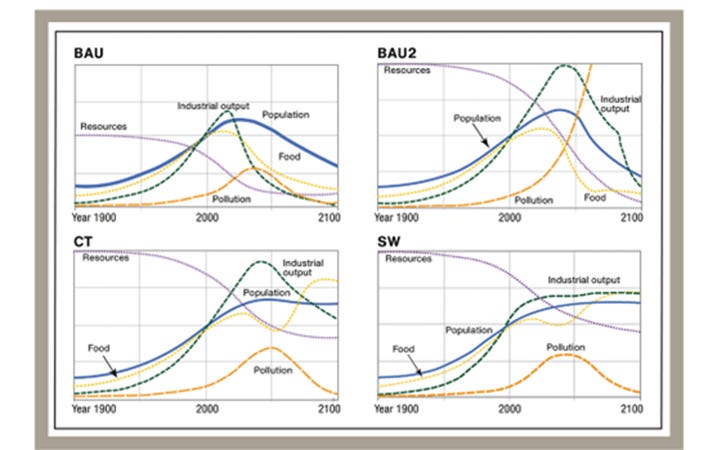

They looked 100 years into the future using advanced computer simulations and, in 1972, they published their ground-breaking report “Limits to Growth”. In it, they presented and analysed 12 scenarios that showed different possible patterns, and environmental outcomes, of world development over two centuries from 1900 to 2100.

The message was clear.

If nothing changed, collapse would begin in our lifetime.

Two scenarios held promise, though. The Stabilised World model (behavioural change and value shifts) and the Comprehensive Technology model (massive investment in sustainable technologies). But both required early action.

Instead, we doubled down.

By 1992, we had overshot our ecological limits in many areas.

By 2002, we had squandered the 30-year window.

By 2020, independent studies confirmed that we were tracking toward the worst-case “Business As Usual” scenarios with economic and social decline projected to begin around 2030, and systemic collapse by 2040.

And still, the dominant cultural narrative keeps whispering.

Grow.

THE FASTER WE GO, THE BIGGER THE MESS

The world is speeding up and we can all feel it.

For many hundreds of thousands of years, the pace of change for humans was fairly steady, much like a marathon. Life was, to some degree, predictable. Until it wasn’t. The global forces identified in the Limits to Growth are now converging, and accelerating.

We can see this acceleration in even the basic human act of communicating:

• Movies cuts were 12 seconds in 1930, now they’re 2.5 seconds.

• Netflix lets you watch at 1.5 times faster speed.

• Audible lets you speed up book reading by 3.5 times.

• The average podcast listener chooses 1.5 times the original speed.

We are all taking in five times more information each day than we did in 1986, that’s about the equivalent of 175 newspapers.

But it’s worth asking … why?

Why, in the face of slowing economies and increasing environmental harm, why are we racing to accelerate everything. From technology, to production, to consumption, and consummation?

Sure, speed can be exhilarating. That’s why we love roller coasters.

And it’s easy to get swept up in momentum, in the thrill of chasing the “world-leading” gold ring. But we don’t notice how quickly each jump in pace creates a new normal. How what once felt extraordinary becomes the new minimum standard, just to stay in the game. Just look at American Idol as a micro-example. The entry standards between when it first aired to this year’s season are phenomenally different, and that’s just 20 years of change.

We don’t recognise that we’ve fallen into a multipolar speed trap. A system where no one can afford to slow down, because slowing down means falling behind.

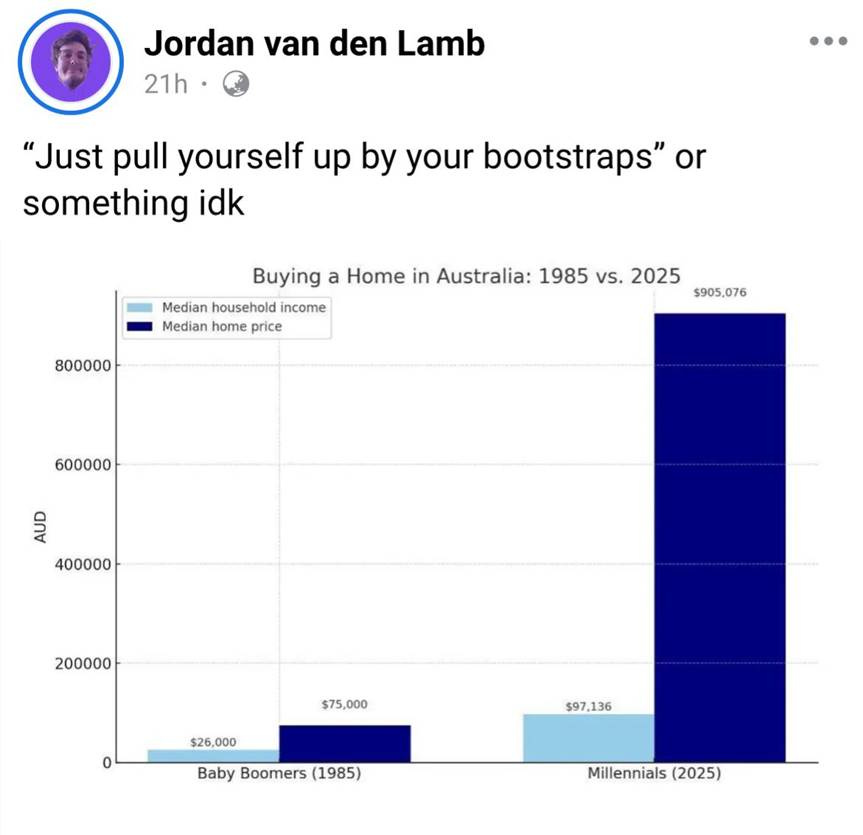

A university degree used to guarantee a job.

A minimum-wage job used to guarantee a home.

Now? Nothing guarantees anything.

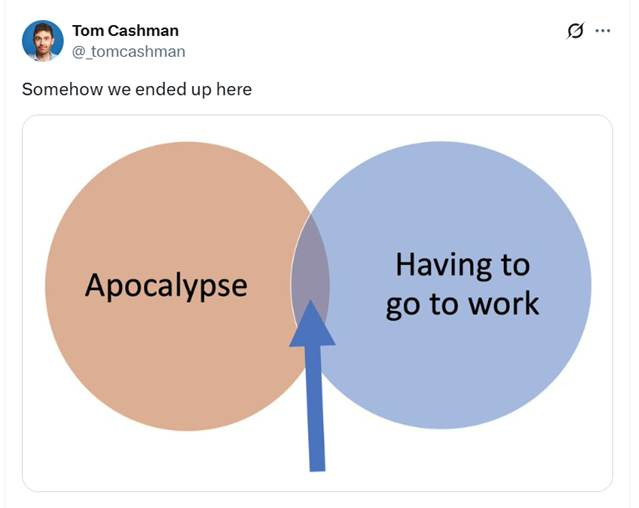

Somehow the speed doesn’t feel exhilarating anymore. It feels terrifying, because we’re no longer in control. Like we’re all trapped in the back seat of a clapped-out Nissan Sunny, driven by a methed-up bogan with one hand on the wheel and the other on a beer. Going the wrong way down the road. With the lights off.

So, if this kind of speed isn’t fun, why do we glorify it?

Arguably, it’s not about “progress” or excitement at all.

Maybe our obsession with speed is a superficial way to manage our cognitive dissonance. A desperate attempt to reconcile the fact that we see the risk, feel the burnout, know the system is unravelling … but don’t know how to get out of it.

So, perhaps “speed” isn’t something that we’re choosing, or even something that we’re aspiring to. Perhaps it’s a deep-seated, fear-based response.

A psychological reaction to growing scarcity.

IT’S NOT A RECESSION, IT’S A RESET

I’m not an economist. And I’m not claiming to be a macro-strategist or a systems analyst. What I am is a pattern watcher, and I’ve been picking up some of the threads that are running through the economic data.

And what I’m seeing isn’t just stagnation or recession.

I have an uneasy feeling that what we’re experiencing with the ‘cost of living crisis’ and ‘local government rates rises’ isn’t just another temporary dip. It feels like it’s more than that. Like the global engine of growth itself is starting to sputter.

I’m hearing of venture capital partners quietly cashing out, and some firms pausing new investments altogether. Earlier this year, Peter Zwyssig talked about how the number of active VC firms peaked in 2021 at around 8,000. But 2024, that number shrank to just 6,000, marking “one of the most significant contractions in recent history.”

Still, the dominant narrative persists.

This is temporary.

We’ll be “back to normal” soon.

But Kate Raworth talks about the fallacy of infinite growth in her magnificent book Doughnut Economics, arguing that our current economic system is built on the absurd notion that Earth’s resources are infinite. But they’re not.

So, perhaps the current economic slowdown is evidence that there’s no such thing as infinite growth within a finite system.

And perhaps the curve isn’t bouncing back because we’ve already reached our limits.

THE AGE OF PANIC BUILDING

What if we are entering a new era.

An era that isn’t defined by abundance, but by panic.

A blood-knuckled scramble to extract what remains.

Because it certainly feels like we’re operating in a kind of anxious frenzy. Panic-building companies and ventures on a global scale. Like stripping the shelves of toilet paper in the pandemic, only worse.

Moving faster not because the world is abundant, but because it is running out.

If you haven’t read the RethinkX report “Rethinking Humanity” then you’re missing out on some really crunchy insights. In it, they note that societies don’t tend to adapt when their systems start to fail. They tend to double down on what has worked in the past. Even though this only makes things worse.

“More extraction, more walls, more blood sacrifices, or more power for the center of authority, be it king, emperor, or the elites that endorse them [..] The negative feedback continues as taxes and debt increase and currencies are debased, selling the future to pay for the present, further destabilizing an already brittle and unstable system.”

THE GAME IS CHANGING

None of this means opportunity disappears. But the rules are different now.

There will still be wealth created in the final stages of the growth economy. Almost certainly there will be enormous wealth. But it will more than likely be captured by the big players who already control supply chains, infrastructure, and capital. The ones already at the top of the food chain who are well positioned to consolidate further.

The window for the rest of us is narrowing.

The idea that anyone with a laptop and an idea can build the next unicorn was always an aspirational myth. Now, it’s a deeply destructive one. The real cost is carried by founders with burnout, chronic anxiety, and despair.

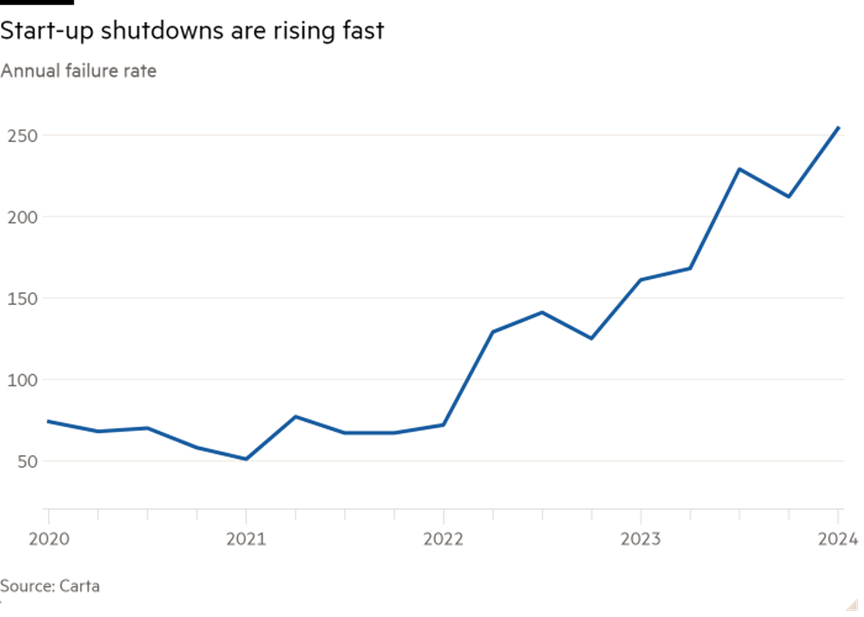

Worse still, recent years have seen a surge in startup failures, with commentators suggesting that 2025 could be another “brutal year” for startups shutting down.

Which all means that founders are now expected to work harder, grow faster, and absorb more risk, just to maintain their seat in a game whose odds are deteriorating. In this environment, the unicorn myth doesn’t just distort expectations. It acts like the Skeksis extracting life force from Gelflings. It erodes wellbeing, papers over systemic failures, and glorifies a model that increasingly delivers diminishing returns.

Yes, exponential growth still exists. But it’s gated. It demands scale, speed, and sacrifice, and the costs are rising.

So, we need to recalibrate.

Not out of fear, but out of realism.

And a solid helping of hope.

WHAT DO WE BUILD INSTEAD?

What kind of ventures thrive in an age of contraction and consolidation?

Well, unless you’ve got access to an emerald mine, the answer isn’t bigger. It’s better connected.

Instead of chasing billion-dollar unicorns, we need to back multi-million-dollar strong ponies. This isn’t any less ambitious, it’s just less delusional. We need to build the kind of resilient, connected enterprises that are here for the long haul. Businesses that grow slowly, serve real needs, and provide real value. Not hype.

There’s a lot to unpack here, so over the next few weeks I’ll be dig deeper into what this shift really means. How we go from panic-building to purpose-building. From extraction to exploration.

I’ll be asking questions like …

What signals tell us the economic slowdown is structural, not cyclical?

What’s really happening with startup and venture investment?

What does it look like when supply chains dry up?

What can we learn from those who’ve already lived through it?

And, most importantly, how do we build businesses that are lean, layered, and local? The kind that last.

See you in a couple of weeks.

I’ve got some thinking 🤔(and a bit of foraging) to do.