#4 The Machine Made of Men

The machine is breaking down. The human mind is breaking free.

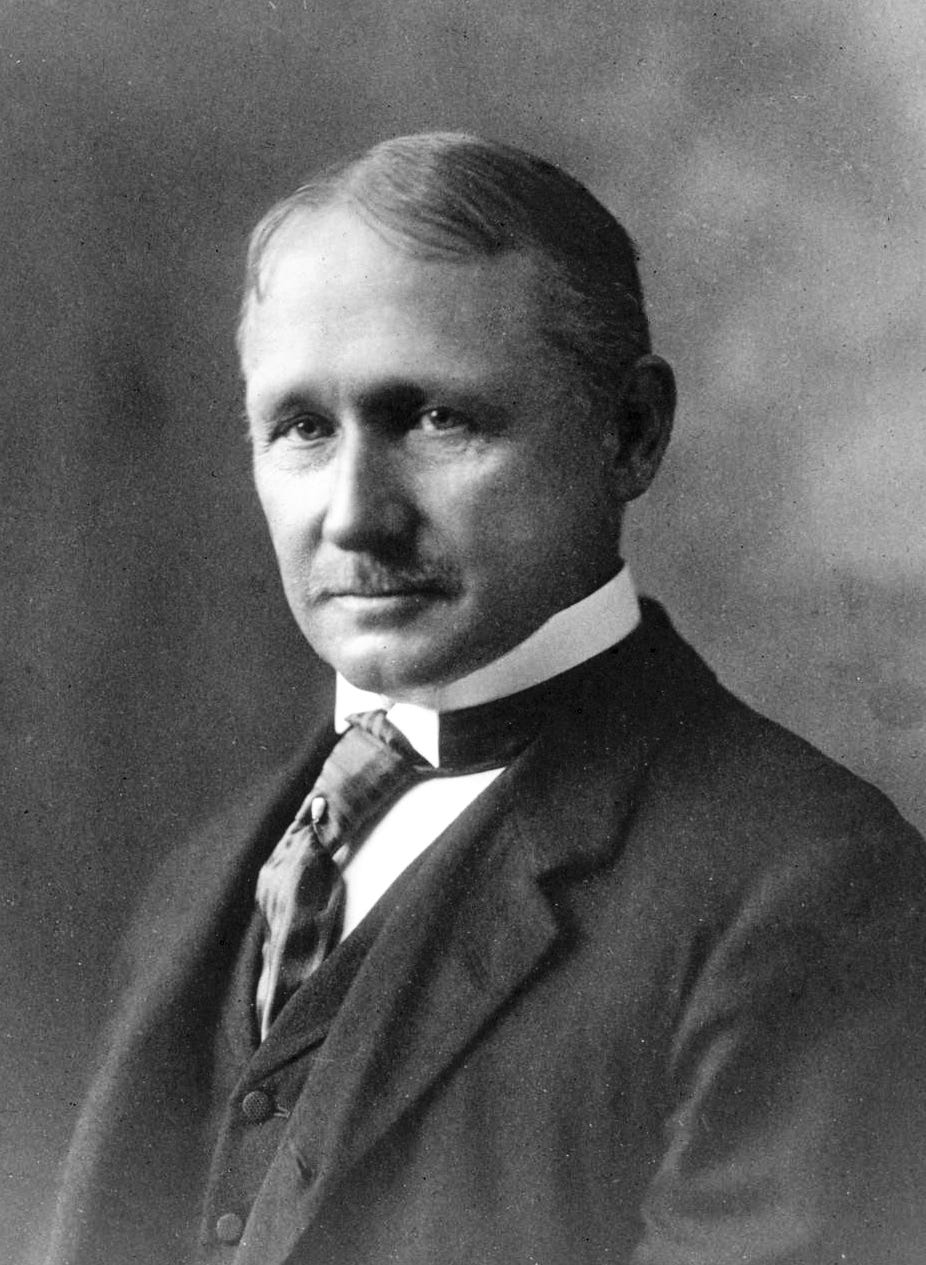

When Frederick Winslow Taylor stepped onto the factory floor in 1881, stopwatch in hand, he was quite literally a man on a mission. A mission from God.

His father was a Princeton-educated lawyer, but he rarely worked. He lived a life of leisure thanks to a sturdy inheritance. His mother was a fierce abolitionist and reformer, though, who preached the gospel of work as a moral duty.

Under his mother’s care, Taylor’s worldview was constructed of Quaker and Puritan values, where discipline was virtue, idleness was sin, and self-mastery was the highest good. So, even though he was born into comfort, Taylor was raised to resent it. And, from an early age, he was determined to forge his character through work.

When Taylor was just 22 years old, he began work as a machine-shop worker at Midvale Steel Works in Philadelphia. He wasn’t there out of need. He was there by choice, as a test of character.

Within a few short years, he rose to foreman, and with it, found his true calling: Not just working hard himself, but reshaping how others worked. By force, precision, and control.

Taylor was morally outraged when he started to see what he termed "soldiering", workers deliberately slowing their pace, conserving their energy. He saw the factory not as a community of craftsmen, but as an undisciplined mob in need of control.

Left to their own devices, he believed, workers would coast.

Waste time.

Think too much.

And Taylor was determined to fix them.

With his ever present stopwatch, the young man broke down every task into its smallest possible components. Every lift, twist, turn, and haul was dissected. He pioneered time-and-motion studies, shaving away every wasted second. And he promised that if you simply trained men to obey the system, to replicate the movements assigned to them, then output would soar.

And it did.

Productivity rose. Factory owners grew rich. And Taylor became famous.

But something else was born in the process.

A machine made of men.

The Gospel of Motion

In Taylor’s world, the worker wasn’t a thinker. They were a cog. Their value wasn’t in their judgment or insight, it was in how well they could deal with the “grinding monotony” of his reinvented ways of working.

Taylor didn’t just make work more efficient. He dehumanised it.

“Now one of the very first requirements for a man who is fit to handle pig iron as a regular occupation is that he shall be so stupid and so phlegmatic that he more nearly resembles in his mental make-up the ox than any other type. The man who is mentally alert and intelligent is for this very reason entirely unsuited to what would, for him, be the grinding monotony of work of this character.”

F.W. Taylor, 1911. Principles of Scientific Management.

This wasn’t a one-off comment. It was a philosophy. An ideology. Taylor’s system was built on the belief that true efficiency required the suppression of human intelligence. That to build a perfect factory, you first had to reduce people to obedient, unemotional, beasts of burden.

Managers were overseers of output and tasks were compartmentalised. Workers were no longer asked to understand the whole, they just needed to master their fragment. Taylor’s stopwatch became the unblinking eye of modernity.

And we are now living in the systems that grew from this ideology.

Because Taylor’s scientific management system didn’t just shape factories. What became known as Taylorism reshaped everything.

His methods spilled out of the factories and into education, where curriculum designers applied the same logic to classrooms, dividing learning into timed units, emphasising rote skills, discouraging deviation. They showed up in corporate structures, where employees were trained to perform repeatable functions, and success was measured in metrics. Then bled in healthcare, where a doctor’s relationship with a patient was transformed into neat 15 minute transactions.

And slowly, across factories and offices and classrooms and hospitals, a new truth settled over the world. Your value was determined by how well you fit the machine. How well you could bear the grinding monotony.

So, when so much of the modern workplace is built on this foundation of dehumanisation, is it any wonder that so many of us feel like cattle?

Yippie-ki-yay ...

The System Isn’t Broken, It’s Working As Designed

The ghost of Taylor still haunts us today.

Does the name Peter Drucker ring a bell? Famous management consultant and strategist. He was celebrated in BusinessWeek magazine in 2005 as “the man who invented management”. Well, he reckoned that Taylorism was “the most powerful as well as the most lasting contribution America has made to Western thought since the Federalist Papers.”

Clearly, the stopwatch hasn’t disappeared. If anything, the expectations have multiplied.

We may not work longer hours than our parents, but the cognitive load has exploded. We’re processing more, switching more, and staying ‘on’ far beyond the end of the workday. We now process up to 74 GB of information a day, a 350% increase from the 1980s.

We’re not just answering emails, we're managing Slack threads, Teams chats, DMs, dashboards, inboxes, calendars, workflows, and whatever the algorithm throws at us next.

We have never carry this much weight before.

Yet we are relentlessly herding people like cattle, and wondering why they collapse. And when they do, we treat it like an individual failure. A lack of resilience.

But maybe rising rates of burnout and mental distress are not because people are “stupid and phlegmatic.”

Maybe it’s because we were never built for this.

We were built for complexity, for drift, and for daydreams.

We innovate through chaos, not mechanical repetition

We thrive in spaces that allow for intelligent variation.

Taylor couldn’t see that.

But we can.

Because we are no longer standing at the rise of the machine age.

We are standing at its fall.

The Rise of the Human Mind

Almost anything that can be standardised can now be done better by a machine. Any task, any thought pattern, any routine. Machines will do it faster, cheaper, without fatigue, without deviation, and without doubt.

The machine made of men has achieved its goal. But in doing so, it has now outlived its purpose.

So I say, let the machines inherit the predictable work.

I’m more than fine with that.

Because the future does not belong to standardisation.

Evolution is born of variation.

So what remains.

What rises.

Is us.

Our future will not be built by those who copy-paste the old systems.

Because the systems we inherited were built to suppress variation.

And what we build next must be designed to unleash it.

Our future will be shaped by those with uncontrolled imagination.

By the ones who still know how to think in wild patterns that no algorithm can replicate.

The age of human mind is rising once again.

But let’s be clear - we are not entering a new era.

We are simply remembering who we were built to be.

Before factories.

Before clocks.

Before grinding monotony.

The same intelligence that once carried us across oceans, and deserts, and unknown lands. The force that built tribes, cities, and civilizations. Danced around fires. Painted on cave walls. Carved meaning into bone and stone and song.

It is stirring again.

Because maybe the burnout isn’t a breakdown.

Maybe it’s a protest.

And maybe the rising tide of mental distress isn’t dysfunction.

Maybe it’s a refusal.

Because what we’re witnessing - in our workplaces and our schools and our hospitals -isn’t just rising absenteeism, or quiet quitting, or disengagement. It’s an entire generation stepping back from a system that demands too much and gives too little.

So, maybe the human mind isn’t just rising.

Maybe it’s rebelling.

And remembering what it is built for.